[DCB] La Mulana

19 6月 2024

YOU ARE IN A MAZE OF TWISTY LITTLE PASSAGES, ALL ALIKE.

Curse of IRON PIPE

The La-Mulana remake manual opens with a folk ballad that echoes the cries of a mysterious feminine being pleading with her children to "let me return home to heaven / it is where I belong." Lemeza Kosugi, an Indiana Jones expy, has received word from his father that the ruins of La Mulana have been found. This may hold the original secrets of where all human civilizations came from.

Unfortunately, the immigration authorities have confiscated everything that might be useful to Lemeza's archaeological work, with the exception of his whip. His father has also been missing for days. If he wants to survive, he'll have to gather as much information and upgrades as he can from the ruins.

When I finally took control of Lemeza, I noticed that he walked around like he had a tank in his pants and jumped like he was a cargo ship that couldn't be steered in the opposite direction. His whip felt weak and short compared to the Belmonts in the Castlevania games. I concluded that he was deeply unprepared to take on the discovery of the cradle of humanity, and took about nine years off before picking up the game again for the Kastel Notebooks project.

I was unused to this kind of player-hostile design, especially if it was platformers. Although I enjoyed some difficult games like Shin Megami Tensei: Nocturne at that time, I was only confident in RPGs. Platformers like I Wanna Be the Guy and Asakura P! unnerved me. I thought I'd never get good at these kinds of games, so I was content to watch people play them on Games Done Quick.

But when people were gassing up Distorted Travesty 3, a difficult but ultimately fair free game, in 2017, I decided to take the plunge. A month later, I finished the game on a crappy membrane keyboard and saw platforming design and boss encounters differently. It opened my eyes to the possibility of abrasive game design that didn't mind putting players through a little bit of hell as long as it could trust the player to get through it and experience the joy of overcoming a challenge.

Since then, I've played all kinds of "difficult" games: hardcore sokoban challenges, masocore-style precision platformers, intense resource management games, expansive interactive fiction titles, and labyrinthine dungeon crawlers. Many games came close to defeating me, but I was always there to welcome them with open arms. I longed for games that hated me as much as I loved them.

I knew I had to return to the ruins of La Mulana. This game had defeated me a decade ago. I thought I knew how to embrace it now.

Mr. Explorer

In an influential essay entitled "The Craft of Adventure", Graham Nelson argues that game designers must constantly worry about the player's journey through their game. Whereas a reader would read a book from beginning to end, a player could theoretically break the sequence and reach the end, or get stuck in a puzzle and never finish. He also emphasizes this point in narrative design: "Our player should walk away thinking it was a well-thought out story: in fact, a novel, and not a child's puzzle-book."

I've always found this article enlightening because I often find myself disagreeing with its most salient points, even though I agree that the most interesting game design analysis is oriented around players. Nelson sees adventure games as "a crossword puzzle at war with a narrative," so he idealizes a balance that ultimately favors the player. It makes for a smoother and more cohesive experience, and I personally don't see anything wrong with that. I just don't find the titles with this philosophy to be as engaging and memorable.

In fact, what I love about old adventure games is that they treat progress as a kind of luxury. It doesn't assume that players can complete the game. Instead, it prefers to be an enigma, which allows people to imagine what can be done to advance the game state. Its impenetrability means I can't know everything with just a few well-timed presses, so I have to speculate about what it's trying to hide.

Rather than being a novel or a child's puzzle book, the old adventure games I love evoke a kind of ellipsis that makes me marvel at how little we know about something. When I spelunked in ADVENT, I wasn't looking for the harmony of puzzles and prose but to see how deep and strange the abysses would go. The puzzles were there to keep me from seeing everything, so I had to be patient and figure out what to do next. I liked imagining what might be on the horizon more than the gameplay itself.

What I want is friction: I need games to stop me in my tracks, to make me rethink how I've been approaching gameplay and narrative, and to remind me that I'm playing something that demands my attention. When I find myself cruising through a game, I treat it like comfort food -- nice to have once in a while, but I can get sick of gorging on it for too long. Such games, even if I play them in the appropriate mood, will not earn my respect as a video game.

La-Mulana wants to body me no matter what mood I’m in. It’s consistently violent to its players and it will never back down. I must train myself to receive its blows.

In retrospect, the game is not difficult. Once you get used to the jumping and whipping, the platforming and boss encounters won't destroy you. The bosses go down easily, and even the hardest fights have simpler patterns compared to recent games.

But its notoriety as one of the most difficult games is justified once the player realizes they have nowhere to go. They may have access to four dungeons, but that doesn't mean they can progress.

It was easy for me to pick up where I left off because I gave up on the game pretty early on. I started wandering around the dungeons, reading the tablets that told the tragic story of the giants, and examining the gods of the oceans with my handy scanner. It took me longer than I thought to solve the first puzzles, but I was hooked.

Grand History

I felt like I was playing an old computer adventure game, trying to figure out how to steal an egg from a hawk. Except the puzzles are integrated into the lore and setting around it.

I started a thread on my Discord server where I took copious notes and screenshots of everything I saw in the game that I found interesting. After each session, I would scroll through the thread's backlog to see if any screenshots of unsolved puzzles were worth revisiting. I would write down what I thought the story was about, why the dungeons were designed the way they were, and whether or not I thought something was a solvable puzzle.

Anything I saw might be important in the long run. A clue I found in the first hour might be crucial to a puzzle in the 90th hour. Or it might not. Still, it pays to fixate on details because you never know.

As I scribbled down my thoughts and observations, a picture began to form. I read the laments of history on the walls, speculated on what the symbols of a forgotten language might mean, and battled the heroes and villains of the past. Everything I did and noted culminated in a grand tragedy, a tale of being trapped in the annals of history and wanting to escape its legacies.

Similar to other colonial archaeology simulators, the game dabbles with ancient astronauts, the conspiracy theory that belittles the technological achievements of prehistoric civilizations by suggesting that aliens did everything. However, I found La-Mulana's take rather unique. The folk ballad introduced in the manual and the lore you read in an early dungeon do not portray an otherworldly omniscient being, but a tragic figure surrounded by children who want her power.

There are no cutscenes in the game and everything is told through setpieces, puzzles, and tablets, but I regardless found the story compelling. Solving a hard puzzle meant that I understood the story and what the game was asking of me, which in turn made me curious about future plot and puzzle developments. I wanted to understand the ruins, the races that once inhabited these cavernous networks, and this alien being in an intimate way.

Wonder of the World

I regarded the ruins of La Mulana as a second home because I was given the opportunity to explore the game on my own terms.

There are many moments in the game where I just stopped progressing. I didn't know what I was looking at, and I would move on, not realizing that I could have solved the puzzle with my current knowledge. Instead, I would solve other puzzles that I had previously struggled with, or simply read stone tablets to re-evaluate what I know.

This downtime was frustrating. I didn't know how long the game was, and I didn't know if what I was fixating on was an actual solvable puzzle. All I could do was look back at what I'd written.

But I appreciated being stuck because I was clearly engaged with the game. All of these negative emotions that the game evoked were proof that I was being affected by the game. I may have found these sections excruciating in the game, but they allowed me to rethink my approach outside of the game. I began to obsess over the title and the ruins.

This obsession paid off when I started unlocking key items. New weapon upgrades and movement options felt magical to me. Enemies I found problematic go down so easily, and I was able to fix my terrible jumping with a few tricks. The ruins in my imagination expanded the more I discovered new shortcuts and tools. I couldn't stop playing the game because the new puzzle I stumbled upon might contain a needed health upgrade or something else I might find useful.

The game became even more fascinating when I started thinking the possible routes a player could've taken. The nonlinearity of the game meant that players could take about the same amount of time and make a similar amount of progress, but they would have seen very different things.

Indeed, a friend and I were playing the game at the same time, but we took radically different paths. Not wanting to spoil each other, we vaguely gestured that we had made some progress and congratulated each other. Anything more explicit and it would dramatically change how we view the ruins into something that doesn't reflect how we explore the game.

I see La-Mulana as a game about getting lost and wondering what the hell to do next. It was important for me to be overwhelmed and reassess what I'd seen. I looked forward to each new tablet and setpiece that would give me some clue to a future puzzle. And it was exciting when memories of things I learned hours ago would suddenly flash up and say, "This is how you solve the puzzle." If I took shortcuts, I would be cutting myself off from those eureka moments.

This is probably the most controversial aspect of the game and why people end up quitting in frustration. The puzzles are "bullshit" by today's standards, and there are "better" games out there, so why am I playing a game that imitates the jank of yesteryear? There are persuasive arguments I can employ, but I think it's valid to think that La-Mulana is not for you, even if you finish the game. I had to use guides after 70 hours because I didn't know how to approach some of the harder puzzles. It is, by definition, an inaccessible game, and it makes no apologies for being so.

But this cycling through the feelings of being lost, utter confusion, and awestruck wonder is what I find most exciting in adventure games like La-Mulana. Contra Nelson, I treat games that don't put up much of a fight as a series of unrelated events, like a theme park. Instead, I value the stream of consciousness where I'm stuck on a puzzle and keep thinking about it before I finally solve it. I can't speak for all players, but I know that when I go through something more streamlined, a little disruption can take away the illusion of coherence in games. If the game world is always hard on its players, then accidental breaks in the flow of the game will be masked by the pain the players have always been experiencing. And when progress is finally made, it feels so deserved that I am totally impressed with my own actions.

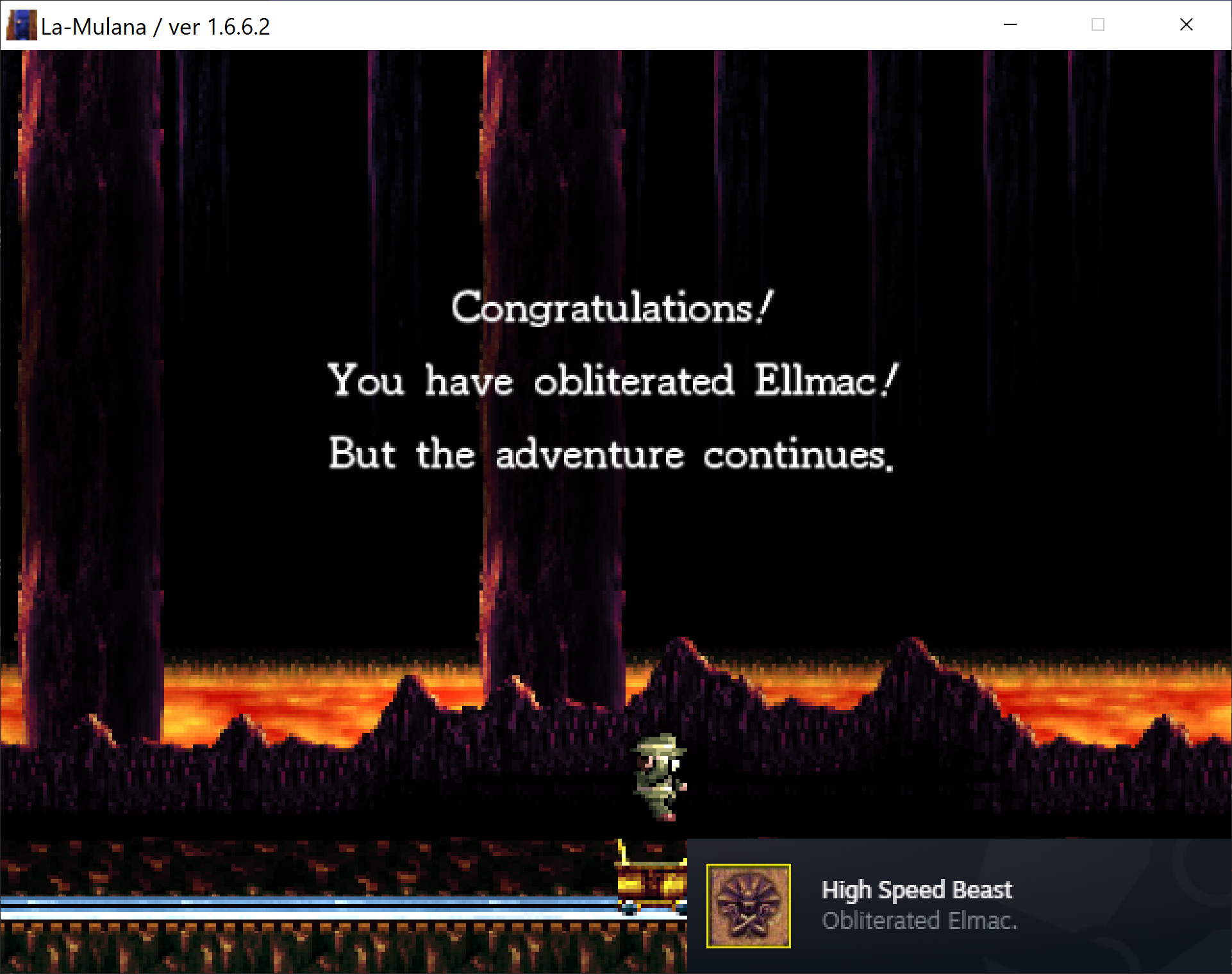

By the end of the game, I saw my Lemeza character as the culmination of all my efforts to grab everything I could find. The hours of long grinding against the puzzles and bosses, not the concerted efforts of NIGORO's developers who made this impressive game, created my La-Mulana adventure.

The bouts of anger, despair, and joy defined the game for me. I cannot have this game any other way.

Song of Curry

So, I think I love this game. I'm not sure if this game changed my life, but I think it epitomizes the game design philosophies I adhere to the most. Almost as if it validated my thinking post-Distorted Travesty 3.

I felt alone playing modern interactive fiction and games because they lacked the cave-crawler magic of ADVENT and the Zork games. I loved these games for reasons unknown to practitioners and theorists of the adventure game medium, let alone other players. The video essayists I was watching were promoting design principles and storytelling ideas that alienated me, so I thought I should try to be content and allow myself to be a kind of solipsist.

I didn't expect people to really understand me beyond my admiration for the Soulsborne series. I have only been able to talk to a few friends about a few games here and there. Even after writing this article, I expect people to be completely confused by the tone of this article.

But I found a kindred spirit in La-Mulana. It captures what I love about video games in one incredible package: the pleasure of overcoming masochistic challenges, the brain-bending puzzles of old adventure games, and the evocative writing that suggests a larger world beyond the executable file.

Perhaps, it's telling that the first thing I did the morning after beating the game was install the randomizer. The game continues to excite my imagination, and the randomizer continues to show me new things the game is capable of. The dungeons feel different every time I start a new session, even though I know items and NPCs are just being shuffled around.

I cannot break the illusion spell that the game has cast on me. It feels massive and alive. I am getting hyped to play more randomizers of it and it feels impossible to write how much I love this game.

All I can think now is that La-Mulana is everything I want from ADVENT and some more. It's an inspiring title that revives the spirit of old adventure games, and I'm now looking forward to playing everything NIGORO makes.

The game is available on Steam and GOG. It is also available on modern consoles, though there are some version differences. This game was recommended by Saori as part of the [#jp_media community backlog](../posts/2024-04-10-The Discord Community Backlog.html).